Civil War POW Camps

Mike Wright wrote, “On both

sides of the war, men and women were locked away in dark prisons or held in

outdoor camps under blistering sun and freezing snow. They were fed too little

and lived and died under primitive conditions.”

[1] There were approximately 193,743

Northerners and 214,865 Southerners held during the war. Over twelve percent of

the prisoners died in Northern prisons while over fifteen percent died in the

South. This is attributed to the superior hospitals, physicians, medicines, and

foods available in the North. Consequently, there should have a notable

difference in favor of the Union.

[2] Roughly, 56,000 prisoners died during

their captivity – 30,000 Union soldiers and 26,000 Confederates due to the

failures of the incarcerators to maintain proper shelter, or provide adequate

food and medical attention. Both sides of the conflict concealed the horrific

conditions that existed in the camps. Author Reid Mitchell asserts that the

topic of Civil War prisons is the “least studied subjects relating to the Civil

War.”

[3] Perhaps it is because it set an egregious

precedent for the treatment of “enemies” in subsequent U.S. wars.

The Confederates were

barely able to procure food for their military and thus it was not a high

priority. The North had a better distribution and administrative system. Prison

guards, in both the North and the South, were frequently poorly disciplined Home

Guards who were unqualified for other more responsible positions. Captives were

confronted with questionable personnel and arrived at conclusions about their

captors based on the example of those patrolling the prison fences.

[4] This may be the case in any prison

environment, deliberate or incidental.

Andersonville

Though we typically only

hear about the horrors of Camp Sumter, also known as Andersonville, both the

North and the South had prison camps. Together there were more than 150 POW

camps. Some of them may have been old forts, buildings or warehouses. Some camps

provided tents; others provided no shelter. The camps were more deadly than the

war. The skeletal survivors of the camps resembled survivors of the camps, both

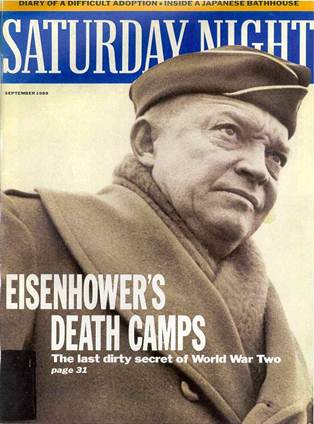

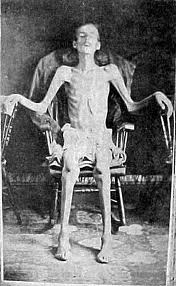

National Socialist and Eisenhower’s camps following World War II.

[5]

After winning the Battle of

Chattanooga, some of the federal troops wanted to continue to

Camp Morton, a Precedent

Northerners are quick to

point the moral finger of slavery and Andersonville which often silences any

reasonable dialogue. Yankees compare Andersonville with the National Socialist

camps. Any media presentation of POW camps during this fateful war focuses on

Andersonville at the exclusion of the North’s hellish Camp Morton. The Union

tried, convicted, and executed Henry Wirz, the commander of Andersonville, for

alleged crimes that occurred before he took charge of the camp or while he was

away from the camp due to illness. The Union called 160 witnesses to testify

against him. Of those witnesses, 145 testified that they had no knowledge of

Wirz killing or mistreating anyone. Only one witness could provide the name of a

victim Wirz supposedly killed. The Union did not allow key defense witnesses to

testify while the prosecution handpicked witnesses to solidify their case

against Wirz. The Union gave its most convincing witness a written commendation

and a first-rate government job. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton reported that a

higher percentage of Southern POWs died while incarcerated than Northern POWs.

[9] The Union hung Wirz on

The Union appointed Colonel

Ambrose A. Stevens as the new commandant of Camp Morton on October 22, 1863.

John A. Wyeth, a Confederate prisoner of the Union, arrived at Camp Morton, near

Indianapolis, Indiana in late October 1863. He survived the camp and went on to

become a physician. Years later, he exposed the horrific conditions at the camp

in the April 1891 issue of Century Monthly Magazine. Other victims of the

camp then came forward and corroborated Wyeth’s disclosures. According to Wyeth,

the Union had erected the camp on about twenty acres of ground that they

formerly used as a fairground. They enclosed the camp by a twenty-foot high

plank wall. There was a rivulet running through the middle of the camp with

sheds on both sides. They initially assembled the sheds to house cattle.

[11]

They built the walls of wooden planks which had shrunk and separated. There were

four tiers of bunks on each side of the “barracks” which extended seven feet out

towards the center. They housed 320 men in each shed. The lowest tier was one

foot off the ground; the second was three feet above the first and so on. The

Union allowed prisoners about two feet each with their heads next to the wide

cracks of the wall with their feet towards the building’s center. The snowy

winter weather in 1863-64 decreased to twenty below zero. Each man had one

blanket. During a storm, snow would usually cover this meager blanket by

morning. The men suffered tremendously as they were unaccustomed to cold weather

which lasted until April.

[12]

Prisoners, walking skeletons, regularly died of starvation on a daily ration

that was not enough for a single meal. The prisoners augmented the meat rations

by harvesting the camp’s rat population. Gangrene resulting in death from

untreated frostbite was an issue. In the crowded squalid sheds, vermin and

parasites were an aggravating challenge. Close personal contact, inadequate

scanty clothes, and no bathing or sanitary facilities contributed to the failing

health and starving conditions of the prisoners, many of which were under

eighteen years of age. The guards physically abused the prisoners who also

suffered constant mental abuse. The sadistic guards immediately shot many of

them or bludgeoned them to death for minor infractions. The guards, possibly for

sport or retribution, repeatedly shot through the flimsy-walled sheds during the

night. Wyeth left this hellhole in February 1865. Two thousand young Confederate

soldiers died at Camp Morton.

[13]

Some of the sheds did not

have bunks, so the prisoners had to sleep on the damp, cold ground in the sheds.

Prisoners, dirty, cold, lousy and emaciated, slept in their clothes to “keep

from freezing.” A Sergeant Pfeifer would walk through the sheds with a heavy

stick thrashing left and right into the heads of the starving prisoners yelling

– “this is the way you whip your Negroes.” Pfeifer was just one of many brutes

who delighted in abusing the POWs.

[14] There is sufficient data to document the

cruelties of camp life at the hands of the Union, during the War for Southern

Independence combined with the ethnic cleansing of America’s indigenous

population. Those simultaneous wars served as a perverse prototype for future

camps and untold millions of victims, all concealed by government policy and

obedient officials.

The Department Encampment

of the Grand Army of the Republic refuted Wyeth’s claims. The department said it

could not imagine why Wyeth and others would fabricate such stories. Century

Monthly Magazine then allowed Wyeth another opportunity to expose Camp

Morton’s horrors. His first exposure brought a flood of articles and letters

published in newspapers nationwide. There were claims that the government paid

contractors to supply adequate food but the prisoners never received it due to

internal theft. Like the Indians, the Confederates were also at the mercy of

corrupt politicians and their crooked cronies.

[15]

[1] What They Didn't Teach You about

the Civil War by Mike Wright, Presidio Press,

[2] Civil War Prisons edited by

William B. Hesseltine, Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio, 1972,

Heseltine’s original work was published in 1930. p. 6

[3] On the Road to Total War, The

American Civil War and the German Wars of Unification, 1861-1871 edited

by Stig Förster and Jörg Nagler, German Historical Institute,

Washington, D.C. and Cambridge University Press, New York, 1997, pp.

565-566

[4] Civil War Prisons edited by

William B. Hesseltine, Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio, 1972,

Heseltine’s original work was published in 1930. p. 7

[5] What They Didn't Teach You about

the Civil War by Mike Wright, Presidio Press,

[6] Ibid, p. 153-170

[7] Civil War Prisons edited by

William B. Hesseltine, Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio, 1972,

Heseltine’s original work was published in 1930. p. 6

[8] What They Didn't Teach You about

the Civil War by Mike Wright, Presidio Press,

[9] The South Was Right by James

Ronald Kennedy and Walter Donald Kennedy, Pelican Publishing Company,

Gretna, Louisiana, 1991, pp. 45-47

[10] What They Didn't Teach You about

the Civil War by Mike Wright, Presidio Press,

[11] Den of Misery, Indiana’s Civil

War Prison by James R. Hall, Pelican Publishing, Gretna, Louisiana,

2006, pp. 57-59

[12] Ibid, pp. 57-59

[13] Ibid, pp. 60-63

[14] Ibid, pp. 79-83

[15] Ibid, pp. 74-77